Beyond the Radar

Fiona Carruthers’ project Beyond the Radar is an ongoing series centred on the significant role that marshlands play in protecting and sustaining human and non-human environments and ecologies.

In the East Midlands of England, Lincolnshire’s marshes are hauntingly beautiful, dynamic landscapes with enormous skies, distant horizons and shifting contours. It is easy to lose yourself (or find yourself) in these ancient sites. The agricultural coastline and land that the marsh protects is valuable as well as vulnerable. It yields about 12% of England’s total agricultural produce including around 30% of the nation’s vegetables and 70% of its fish processing. More than 40% of the county’s land, however, is at or below sea level.

With increased incidents of unprecedented flooding and a greater number of coastal storm surges expected, it is evident that life in Lincolnshire is going to change, and that this is likely to happen within the lifetimes of today’s children. The beyond-human-scale abstract notion of the climate emergency has finally become personal.

‘Part of this project is my ongoing commitment to finding ways of opening-up conversations about the fragility of human and non-human ecologies and communities in this region with new and existing audiences. A greater understanding of how marshland contributes to sustainability will develop a greater awareness of the links between local and global issues.

Here on the coast, the saltmarsh offers vital storm and flood protection, essential feeding grounds for migrating birds and fish nurseries as well as an important breeding site for grey seals. The local benefits of the marsh are easy for us all to see and appreciate. Less apparent, however, is the significant protection that they provide globally. Marsh, like other wetland habitats are vital weapons in the fight against climate change. Wetlands absorb large quantities of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it. Pound for pound, these habitats can store up to 10 times more carbon and at a much faster rate than mature tropical forests. This is their super-power. Not everyone lives close to a saltmarsh, but everyone benefits from their many layers of projection.

An understanding of the consequence of the ongoing global loss of wetlands, which is estimated at between 1–2% per year, offers yet another strong message about the importance of these often-undervalued landscapes – when an established wetlands habitat is damaged the carbon it has held onto in its soils, often for thousands of years, is emitted back into the atmosphere.’

Below the Radar (2021)

Installation views | Stalks, dressmakers’ pins, recycled acrylic tiles and knitting wire

In recent months, Carruthers has been exploring and developing several strands of work for this project. We are highlighting two of these in Points of Return. Based on first-hand research, structured experimentation, imagined futures and remembered survival strategies, each is focused on a different survival solution or storyline, and each embodies something of the self-organising properties of the dynamic marsh landscape itself. Ephemeral materials from the land play a strong role. Below, the artist explains her installations.

On Waiting for the King Tide & Below the Radar

Waiting for the King Tide is a series of sculptural works using ephemeral materials from Lincolnshire’s wetlands, exploring the idea that all matter needs to be securely tethered or rooted to survive the twice daily pull and drag of tidal waters. Adapting for drag and resistance is fundamental to surviving a saltmarsh environment. Below the Radar uses ephemeral stalks, dressmakers’ pins, acrylic tiles, fluorescent lighting and DJI drones. It explores the self-organising nature of the marshland itself. To survive, the marsh will move across the surface of the earth in comprehensible timescales.

These are both on-the-point-of collapse events which rely on the interconnectedness of their elements (and viewers’ amended behaviour) to exist and function. Viewers’ behaviour quickly changes to take account of the fragility and precarity of these works. Visitors visibly slow down and become more spatially and socially aware of their surroundings, themselves, and others. Merleau-Ponty describes this as a reciprocal exchange of question and answer in which sensing takes place as the ‘co-existence’ or ‘communion’ of the body with the world.

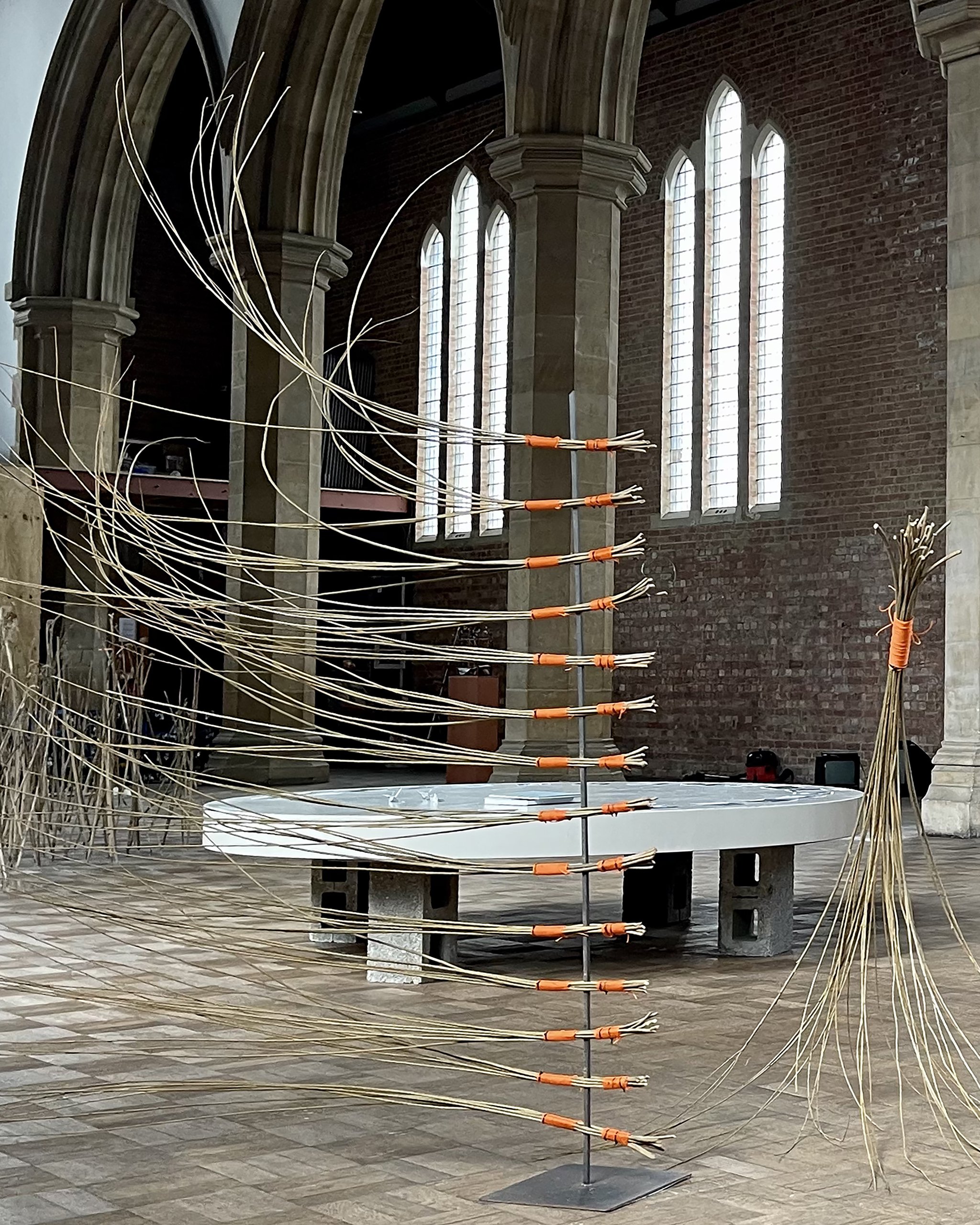

Waiting for the King Tide (2021)

Installation views | Willow rods, lifeboat orange builders’ line, recycled square steel rod and knitting wire

The single willow rods in this work are bound together with life-boat-orange builders’ line. They are tightly anchored to the metal rod (or rather held in place by forces of compression and tension) to achieve a temporary balance. I want to communicate something of the understanding that all matter, human and non-human, needs to be resolutely tethered to survive the constant friction and drag of the ebb and flow of the twice-daily tides of the sea.

In their singular form the willow rods are flexible and easily breakable but together, united, they become tougher, more resilient – impossible to bend or snap. Yet, the top-heavy form of this work is extremely unstable. It is supported precariously by the thin and delicate lower parts of the single willow rods. I particularly enjoy the tension of opposite forces working together to create a temporary state of equilibrium. This, as well as a palpable precarity contributes to the work’s sense of movement and change.

The accidental drawings created by the liveliness of the willow successfully carry the eye above and beyond human scale to trigger new connections between the work, the building, and the viewer. Their lightness and triviality and even their delicacy are the very things that give them worth. In their compelling vibrant spread, I discover a renewed awareness that gravity’s irresistible pull on all things effects and connects human and non-human without prejudice.

What I see, feel, and sense in this work is a reminder of being connected to the wider world: my body is not simply in space but lives and inhabits it in relation to the world.

Below the Radar (2021)

Installation footage | Stalks, dressmakers’ pins, recycled acrylic tiles and knitting wire

Below the Radar (2021)

Installation footage | Here the artist is using the single red light of a builder’s laser level to draw closer attention to the unique properties of the ephemeral material. The red beam becomes disconnected and form, position, and distance in this space becomes more tightly anchored.

The ephemeral material used in this work was gathered from fields in the marshy Witham valley in the heart of Lincolnshire (the site of a prehistoric timber causeway in use between 457 and 321BC). The stalks were assembled and organised to generate the sense of a unified force moving forward through the vast space of the nave. Their inferred migration engineered to reflect the marshland’s own self-organising solution to changes in water levels. A marsh can move itself across the surface of the earth in comprehensible timescales.

The random pattern of the stalks’ dry and dusty-mud taproots lightly touching, or almost touching the floor of the church generate the effect of a syncopated beat. The structure of these forms is elusive, and rhythmical deviations help to create a balance of predictability and surprise. This in turn helps to communicate the idea that this is a natural phenomenon. The forward flowing rhythm of the unique multiples of assembled stalks too, help to pull the viewer from east to west through the nave.

As sunlight floods in from this magnificent building’s windows the installation is transformed. The allusion to water in the reflections on the reclaimed acrylic tiles point to the landscape that the stalks were gathered from and reveal something more about the nature of this site and space. I am again reminded that it is gravity that causes water to move and that the presence of it passing is all around us.

Yellow lighting has been used occasionally, covering everything and everyone without prejudice, bleeding into the very space itself. Alluding to the inescapable soaking properties of water, its poisonous-yellow adds to the sense of a precarious land.

Various lenses have been used by the artist to document and share the story of this work. The fragility, precarity and vulnerability of Waiting for the King Tide and Below the Radar present themselves boldly in the monumental space of the deconsecrated St John the Divine church, heightened by the building’s vast stillness and silence. These works offer us a point of return, highlighting one of the many natural resources we have – if protected – in combatting the climate crisis.

Fiona Carruthers is a Lincolnshire-based artist working in expanded fields of drawing to investigate the posthuman predicament. Her work is preoccupied by insecurity and collapse, and reimagining possibilities for transformation and survival.

Carruthers gained a Fine Art Degree from Sheffield and Post-graduate Diploma from Lincoln. She received the region’s ArtEscape Award in 2019 and, in 2021, was selected for the Sustainability and Environment residency at Lincolnshire’s Museum of Art and Archaeology. Her residency work will be developed further with the support of an Arts Council grant. Carruthers regularly exhibits and contributes to cross-disciplinary events across the region and is an associate artist with Spike Island in Bristol.