AnthropoScenes

To open this third Viewing Room, we’re returning to the work of Adam Sébire. This page looks at the issue of withdrawal, or retreating (melting, calving) ice, reshaped coastlines, and time itself running out. Here, opportunity seems to be retreating from our grasp. In this first work, AnthropoScene I: Breakdown (below), Sébire uses dark humour to document one of Iceland’s fastest-disappearing glaciers, Breiðamerkurjökull. This astonishing iceberg procession is reimagined as a traffic jam of cinematic proportions.

‘Arriving at the lagoon on a bitingly cold winter’s day’, Sébire tells us, ‘I had not anticipated the movement of the icebergs. But it was a tidal lagoon and, if one waited a few hours these sublime entities began jostling for pole position to head out to open ocean. It was both fascinating and terrifying to see geological (specifically, cryological) timescales moving so fast. Ice thousands of years old had only days to “live”: once it hit the ocean. It was attending a funeral procession.’

Only when the artist returned to his studio in Reykjavík and was fast-forwarding through the rushes did he laugh out loud at the sight of these forms zipping around like they were in a demolition derby. As a brief diversion he added the sound effect of a petrol-guzzling vehicle – and the idea was born. Adding layer upon layer of audio to create this peak oil pile-up, he then struggled to find enough sound effects to suggest a path forward via alternative forms of transport. ‘Hollywood sound effect libraries have yet to catch up with the changing world of fossil-free transport, it would seem.’

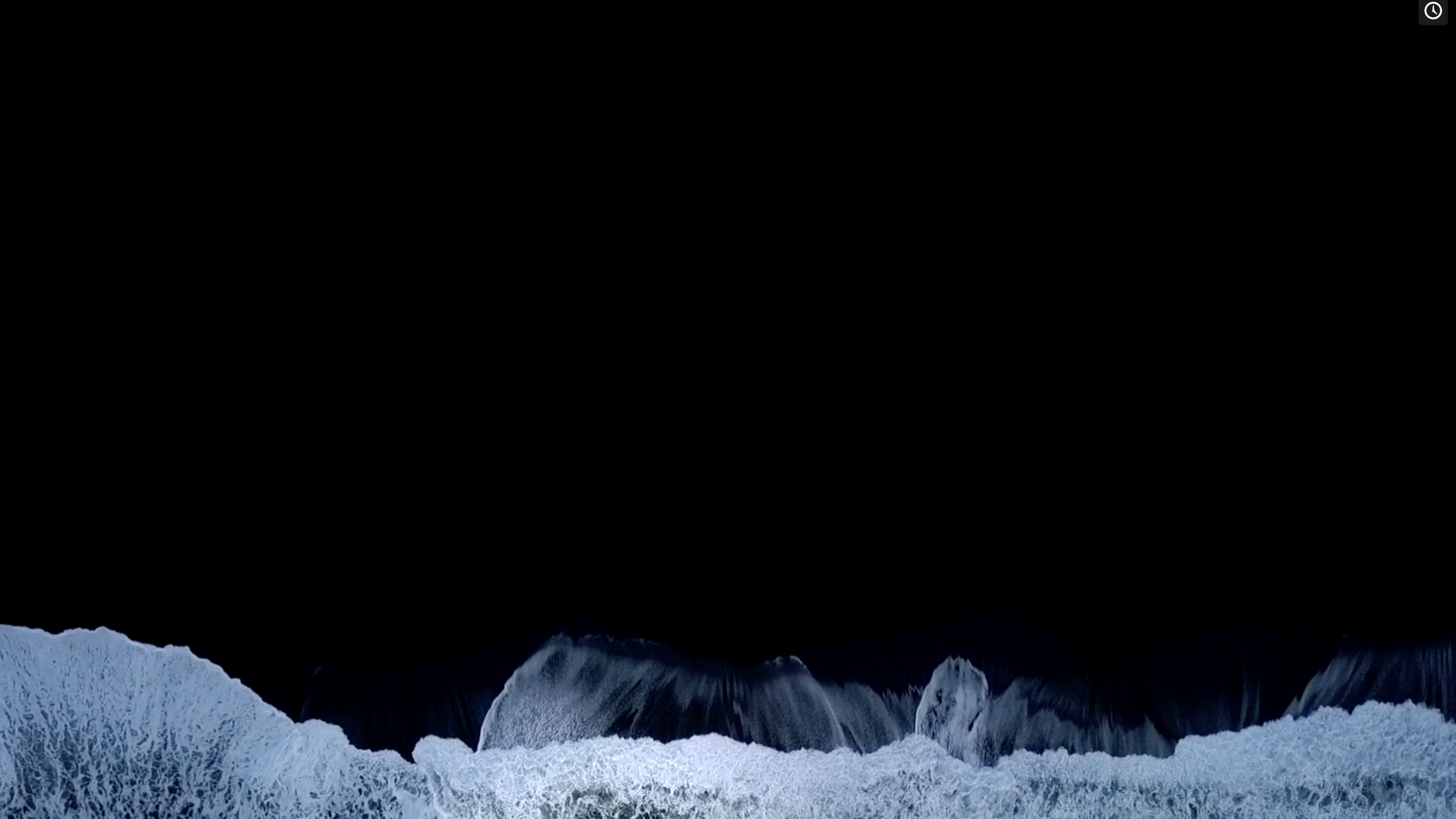

AnthropoScene II: Tideline (below) is filmed with a drone, off remote eastern Iceland. Its reverse slow motion creates an eerie sense of prolepsis; a premonition of inexorably rising sea levels. Initially the work appears almost abstract, as if we are not sure on which plane the terrifying forms are growing. Art critic Andreas Breivik wrote thoughtfully about the film:

‘[Here], there is a confusion about time. The confusion applies to both the material represented and the technique used. Although water is a volatile and liquid material, the water in this work appears as powerful rock chains, and heavy, dense formations, with a large physical presence. These waves are filmed from above, against a black sandy beach, and in the short video work the movements of the waves are played backwards, in slow motion. Thus, the water’s foaming mountain ranges seem to collapse and fall backwards in time, as the video progresses.

This is how the extent of time appears to be unsynchronised, dislocated, and the work provides an opportunity to reflect on a central conflict in the era of the climate crisis: between humans’ short lives and intensive consumption of resources, and nature’s slow, inexorable and eternal process. The work is accompanied by a soundtrack from an instrument made of recycled materials, and although the tone is mournful, reuse and this circular economy point the way out of the climate crisis' most powerful and frightening consequences. Back in the video, the waves have washed out the beach and an area of calm water can be seen, but the line between sea and land is creeping ever higher.’

AnthropoScene III: Hellishei∂i (below) is a speculative artwork, inspired by a contemporary geo-engineering pilot project, again in Iceland. The Climeworks/CarbFix2 project at Hellisheiði is the world’s first industrial-scale “carbon scrubbing” experiment to capture carbon dioxide (CO₂) directly from Earth's atmosphere. This CO₂ is mixed with water and pumped through domed injection wells into the active volcano below it, Hengill, where it becomes petrified as rock.

‘Most climate change policy tacitly assumes the success of such geo-engineering experiments – despite their high cost and unknown long-term consequences. At COP21 in Paris, December 2015, the world’s leaders stated their “aspiration” to limit global warming to an upper limit of 1.5ºC this century. On the planet’s present greenhouse gas emissions trajectory there is no way to achieve this without geo-engineering (sometimes termed climate engineering): using technology – most of it unproven and with unknown potential side-effects – to “modify” our climate.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is arguably the most benign of these technologies. But despite being both difficult and expensive it has proven politically attractive as a “technofix”, delaying decarbonisation initiatives. Indeed all forms of climate engineering potentially come with what ethical philosophers such as Clive Hamilton identify as moral hazards by encouraging continued reckless exploitation of fossil fuels. Worse, many forms of geo-engineering essentially propose that we “hack” the Earth System.

Since October 2017 this other-worldly test site has been capturing carbon dioxide directly from the air surrounding Reykjavík’s geothermal power station: anthropogenic greenhouse gases sequestered in stone. In 2021 the project was significantly expanded. I’m drawn to this site for its modern-day alchemy and for its Promethean overtones: an unshakeable faith in the technological mastery of Homo sapiens.

I chose a triptych form for the screens because, like the millenarian tropes of religious altarpieces, geo-engineering proposes a last-minute, miraculous redemption from apocalypse for those who have faith in the abilities of Modernity’s technofixes.

In this video altarpiece, one of the three screens investigates the experiments at Hellishei∂i; it shows the injection wells of CarbFix2 plus Climeworks’ white cube “carbon scrubber” DAC module, a prototype for what’s expected to be many thousands spread across the planet. On another screen, a core sample of the sequestered CO₂ – now mineralised as calcite within the basalt host rock – appears as a quasi-mystical object in a vitrine. The third screen is more ambiguous: set in a future geological era where complex lifeforms seem to have disappeared. The planet appears to be correcting an atmospheric imbalance; geological processes reverse. After only a few hundred thousand years, homeostasis – equilibrium – will have returned.’

AnthropoScene IV: Adrift ∆Asea-ice (below) asks, what if we could actually see our own contribution to a warming climate?

‘Citizens of developed countries are increasingly aware of correlations between our lifestyles and the climate crisis: witness the phenomenon of flygskam or “flying shame”. Borrowing a groundbreaking scientific formula* I calculate and saw off the exact amount of Arctic sea-ice (15.69m²) that will be destroyed by my carbon emissions flying economy return, from Sydney to Greenland, to film it (5.23 tonnes of CO₂e).

Adrift (∆Asea-ice) visualises and mythologises the consequences of a Western way of life. It touches upon disconnects – of cause from effect; of emissions here & now from melting there & then – that underly our psychological responses to global warming. Disconnects that have perhaps kept the problem comfortably abstract for us – until now.

Notz & Stroeve’s equation – ΔAseaice = dFnonSW,in / dECO₂ x ΔECO₂ – states that the total area of sea-ice lost equals a constant – derived from research into energy flux at the ice edge – of 3.0 ± 0.3 square metres per metric tonne of carbon dioxide emitted, multiplied by the sum of emissions. Inserting my own 5.23 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent into the equation, this works out at 15.69 ± 1.57m² of sea-ice that will not regenerate naturally in northwest Greenland come winter. With less sea-ice to reflect sunlight back into space the ocean absorbs more heat, contributing to even faster warming in the Arctic.

Adrift (∆Asea-ice) is a video vignette from an Arctic tipping point, bearing witness to our own contribution to climate change. Its multiple screens explore cognitive dissonance; cause & effect; human & cryological time. The soundtrack comprises æolian sounds from an empty water tank in the artist’s residence at Upernavik Museum in northwest Greenland that “sings” when it is windy.’

*Notz, D., & Stroeve, J. (2016): Observed Arctic sea-ice loss directly follows anthropogenic CO₂ emission | Science, 354, 747–750

“The artwork, the environmental statement, and the artist flow seamlessly here. The concept, the subject, the object, and the execution coexist harmoniously in an inclusive manner accessible to anyone who is able to sit still and consider. His lateral approach is fresh and gives me hope in human nature once more.”

At the time of writing, Adam was producing a PhD on the visual representations of climate change. En route from Svalbard to Greenland for his research in early 2020, borders snapped shut. Adam was unable to return to his native Australia due to Covid-19 border closures. Now one of the Arctic Circle’s three million human inhabitants, he’s completing his research with a front-row view.

Before leaving Australia in 2019 Adam hand-planted 149 Eucalyptus trees in the dry and degraded soils of his parents’ former sheep farm to soak up the 9.9 tons of carbon emissions his journey was going to create. He must now care for them for the next century.

Adam’s works as an artist-filmmaker-photographer have been shown widely, in international film festivals, museums, galleries and TV broadcasts globally, from Al Jazeera International to the Deutsches Museum to the United Nations in New York. Following a documentary shoot on the Pacfici atoll of Tuvalu in 2003 Adam’s focus gravitated towards climate change. He jumped streams to video art in 2013, frustrated by the television documentary’s reliance on “visible evidence” in the face of a largely imperceptible problem, and one characterised by our own cognitive dissonances.